Blumlein Binaural Sound(1931–1935)

A two-track optical stereo system for 35mm film developed in London by Alan Blumlein, an engineer at Electrical and Musical Industries (EMI).

Film Explorer

Identification

20.96mm x 15.24mm (0.825 in x 0.600 in).

B/W

Unknown

1

Two unilateral variable-area optical tracks, printed side-by-side onto 35mm film, to the left of the image inside the perforations.

“sum” and “difference”.

Unknown

B/W

Unknown

History

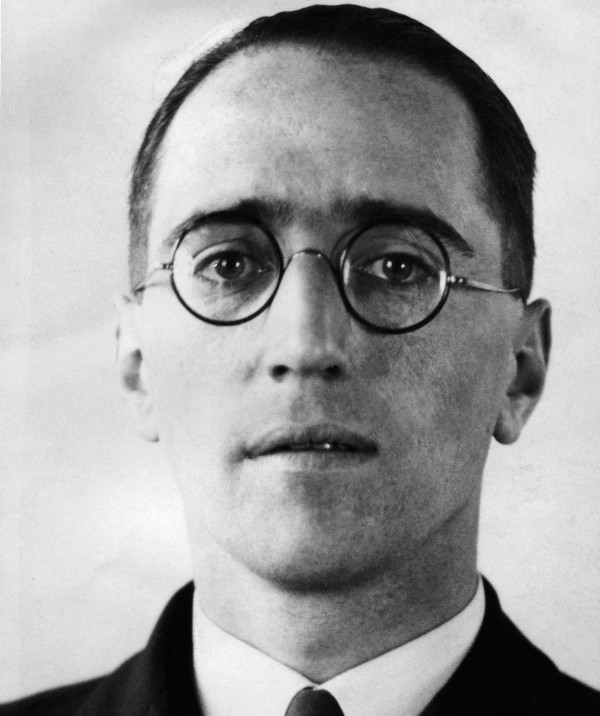

Binaural Sound was a two-track optical stereo format for 35mm film, among the first formats to host an image and two audio tracks on a single filmstrip. It was invented in 1931 by Alan Blumlein – a young audio engineer, who also invented the moving-coil microphone (Blumlein & Holman, 1932), among other recording technologies – and developed under his supervision at EMI’s Hayes factory in London, England, between 1933 and 1935. The project culminated with the production of several short films, designed to demonstrate the system’s acoustic and dramatic potential for narrative motion pictures. However, the films suffered from a number of acoustical problems, most notably the prominence of background noise. And due to limited resources at EMI, which primarily specialized in music recording and playback technology, these problems were never fully addressed, and the format was not developed further for commercial use.

Blumlein reportedly conceived of the format in 1931 after taking his wife to the cinema (Alexander, 1999: p. 60). Like most talking pictures at the time, the film they watched featured a mono soundtrack, where all the dialogue emanated from a single speaker positioned behind the center of the screen, regardless of the actor’s location in the frame. Blumlein found this auditory experience unsatisfying, which led him to envision a stereo theater system where sounds would be perceived to travel between the left and right sides of the screen, in concert with the actors’ movements. That December, he submitted a patent application for such a technology. It outlined new microphone techniques for separating sounds into two signals, new methods for encoding these signals onto optical tracks, and new processes for reproducing these signals through two loudspeakers (Blumlein, 1933). He later named this system “Binaural Sound”.

Once his British patent was approved in 1933, Blumlein enlisted a colleague at EMI, Cecil Oswald Browne, to create a prototype for his new stereo system. The two then assembled a team of engineers from EMI’s sound, film, and television divisions – including Herbert Holman, Ivan Turnbull, Maurice Harker and Henry Clark – to help build the necessary recording and mixing equipment (Alexander, 1999: pp. 81–2). They completed their working prototype in 1935, at which point Blumlein oversaw the production of several test films that would showcase the new format’s capabilities. The films, which were produced at EMI’s research and development factory, included short actualities of trains arriving at the nearby Hayes Station (and passing from frame-right to frame-left), as well as staged demonstrations filmed on the factory’s auditorium stage, where EMI engineers (including Blumlein) addressed the camera while moving across the frame. The final film, produced twice, was a comedic playlet called Move the Orchestra, set in a restaurant, where the conspicuous playing of an offscreen orchestra makes it difficult for customers to place their orders with the waiter. Screenings were held for film industry insiders as well as dignitaries, including the Prince of Wales (soon to become the short-reigning monarch, Edward VIII) (Burns, 200: p. 140).

EMI nevertheless chose to shelve the project shortly after these demonstrations. Studio heads and theater owners had only recently converted to talking pictures, and few had the appetite to invest in yet another costly overhaul of their facilities. Indeed, every attempt to introduce multi-track sound to motion pictures during the 1930s faced similar resistance (Dienstfrey, 2024). Other, rival attempts included the two-track premiere of Hell’s Angels (1930), the limited run of A Midsummer Night’s Dream (1935), in a three-speaker format later branded Vitasound, and Joseph Maxfield’s two-track optical stereo system developed at Electronic Research Products, Inc (ERPI). As with Binaural Sound, studios and theaters had virtually no interest, at the time, in adopting any of these stereophonic formats. Instead, they were focused on improving the quality of their existing mono systems.

EMI also had limited resources. Binaural Sound showed potential, but it was acoustically flawed. The use of narrow optical audio tracks substantially increased the volume of background hiss. Additionally, Humphries’ Laboratories – where the films were processed – had yet to adopt a system that enabled the optical tracks and images to be printed simultaneously. Instead, they employed a two-stage chemical process that resulted in the two audio tracks losing much of their definition and contrast, weakening each film’s directional effects and leading to even more background noise (Alexander, 1999: pp. 85, 91). Blumlein’s team would later incorporate a “squeeze track” process that removed much of this noise (Burns, 2000: p. 510). Yet, even with these improvements in clarity, EMI’s head of research, Isaac Schoenberg, felt that it would be more prudent to invest, instead, in the company’s emerging television technologies (Alexander, 1999: p. 91).

Blumlein subsequently turned his attention to the development of improved aviation technologies. He died on June 7, 1942, while testing a new radar system on a Handley Page Halifax bomber, which crashed near the England–Wales border, with the loss of all those onboard (Burns, 2000: p. 455). Cecil Browne, who helped develop Blumlein’s Binaural Sound system at EMI, also died in the crash.

Selected Filmography

A long-shot of a fire engine driving through a field, passing through the frame several times, as it rings its siren. Single shot: 1 min 16 sec.

A long-shot of a fire engine driving through a field, passing through the frame several times, as it rings its siren. Single shot: 1 min 16 sec.

Two takes of a restaurant scene, in long-shot, filmed on the EMI television stage and performed by the EMI Amateur Theatrical Group. In it, customers attempt to place their order with a waiter, but are regularly interrupted by the playing of an offscreen orchestra, the sounds of which repeatedly move from offscreen-left, to offscreen-right. Take 1: 4 min 13 sec; Take 2: 3 min 33 sec.

Two takes of a restaurant scene, in long-shot, filmed on the EMI television stage and performed by the EMI Amateur Theatrical Group. In it, customers attempt to place their order with a waiter, but are regularly interrupted by the playing of an offscreen orchestra, the sounds of which repeatedly move from offscreen-left, to offscreen-right. Take 1: 4 min 13 sec; Take 2: 3 min 33 sec.

A long-shot of several engineers playing with a small stick on the EMI auditorium stage. Single shot: 1 min 15 sec.

A long-shot of several engineers playing with a small stick on the EMI auditorium stage. Single shot: 1 min 15 sec.

An extreme long-shot, taken at a high angle, of the Hayes Station train tracks as various trains pass from frame-right to frame-left. Single shot: 5 min 11 sec.

An extreme long-shot, taken at a high angle, of the Hayes Station train tracks as various trains pass from frame-right to frame-left. Single shot: 5 min 11 sec.

A long-shot of several engineers casually walking around the EMI auditorium stage, either counting, or reciting days of the week. Two shots: 1 min 36 sec.

A long-shot of several engineers casually walking around the EMI auditorium stage, either counting, or reciting days of the week. Two shots: 1 min 36 sec.

Technology

Like other 35mm stereo formats, Binaural Sound positioned its two optical tracks side-by-side to the left of the image, in the space typically reserved for a single audio track. Further, instead of each track housing the left and right playback channels, the two tracks corresponded to “sum” and “difference” channels, often referred to as middle (“M”) and side (“S”). The M track, centered between the perforations and image, contained the sum of the amplitudes of the left and right channels (expressed as “L + R”). The S track, located between the M track and the perforations, contained the difference in amplitude between the two channels (expressed as “L – R").

During playback, a special processor wired into the projector performed a set of operations (known at the time as “shuffling”, and later known “matrixing”) that separated the left and right signals and directed them to the two loudspeakers behind the screen. To isolate the left signal, for instance, the processor added the M and S tracks together – expressed as (L + R) + (L – R) – which subtracted (or “cancelled”) the right signal, thereby preventing it from playing through the left loudspeaker. And to isolate the right signal, the processor subtracted the S track from the M track – expressed as (L + R) – (L – R)– which similarly removed the left signal.

The use of sum and difference tracks as opposed to left and right tracks offered two benefits. First, it enabled EMI to circumvent the patents that Bell Telephone Laboratories (BTL) held on standard left/right tracks – such as Harvey Fletcher’s 1927 patent for a binaural telephone system (Fletcher & Sivian, 1927) – thereby making it harder for BTL to sue EMI for patent infringement. Second, it intended to make the format backwards compatible. Because the sum track was placed in the same position that mono tracks typically resided, and because the difference track was to the side, a standard one-channel soundhead would, in theory, only read the sum track and thus would play the left and right signals in mono without any loss of information. That said, it remains unclear whether standard mono soundheads did, in fact, only read the sum track, or whether they inadvertently read the outer-placed difference track as well.

Though Binaural Sound failed to become a commercial format, subsequent stereo technologies – including FM stereo and quadraphonic home stereo – drew upon Blumlein’s sum and difference process with much success. Dolby Stereo was arguably the most notable technology to emerge that used ideas similar to Blumlein’s. Developed by Dolby Laboratories during the 1970s, the famed 35mm film format not only featured two narrow optical tracks next to the image. It also used an encoding system – known as the Dolby MP (Motion Picture) Matrix – that was similar to Blumlein’s sum and difference process, allowing its two-track prints to carry four playback channels (left, center, right, and surround). The left track housed the left channel in addition to the sum of the center and surround channels (C + S); while the right track housed the right channel, as well as the difference between the two channels (C – S). Subsequently, when the left and right tracks were combined and sent to the center loudspeaker, the surround channel was silenced. Likewise, when the right track was subtracted from the left track and sent to the rear speakers, the center channel was silenced (Dienstfrey, 2024: pp. 192–4). Dolby Labs never mentioned Blumlein in its discussions of the MP Matrix. The company instead promoted its format as an extension of home stereo technology. Nevertheless, Dolby Stereo’s specific incorporation of the sum and difference encoding process – like other sound systems that featured matrixed audio channels – was unknowingly indebted to Blumlein’s innovations from the 1930s.

References

Alexander, Robert Charles (1999). The Inventor of Stereo: The Life and Works of Alan Dower Blumlein. Boston, MA: Focal Press.

Burns, Russell (2000). The Life and Times of A. D. Blumlein. London: Institution of Electrical Engineers.

Dienstfrey, Eric (2024). Making Stereo Fit: The History of a Disquieting Film Technology. Oakland, CA: University of California Press.

Patents

Fletcher, Harvey & Leon J. Sivian. Binaural Telephone System. US patent US1624186, filed June 15, 1925, and issued April 12, 1927. https://worldwide.espacenet.com/patent/search?q=pn%3DUS1624486A

Blumlein, Alan Dower & Herbert Edward Holman. Improvement in electro-acoustic devices. UK patent GB369063, filed May 13, 1931, and issued Mar. 17, 1932. https://worldwide.espacenet.com/patent/search?q=pn%3DGB369063A

Blumlein, Alan Dower. Improvements in and relating to Sound-transmission, Sound-recording, and Sound-reproducing Systems. UK patent GB394325, filed Dec. 10, 1931, and issued June 14, 1933. https://worldwide.espacenet.com/patent/search?q=pn%3DGB394325A

Compare

Related entries

Author

Eric Dienstfrey is the author of Making Stereo Fit: The History of a Disquieting Film Technology (University of California Press, 2024). His articles on the history of film sound technology have appeared in the Journal for Cinema and Media Studies, Film History, The Velvet Light Trap and Music, Sound and the Moving Image. In 2017 he received the Katherine Singer Kovács Essay Award from the Society for Cinema and Media Studies for his article “The Myth of the Speakers: A Critical Reexamination of Dolby History”. He currently is a professor of film, media, and communication studies at Ursinus College, Collegeville, PA, and the University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ (online).

Thanks to Andrea Comiskey, Katie Quanz, and Kyle Stevens for their comments on earlier drafts.

Dienstfrey, Eric (2025). “Blumlein Binaural Sound”. In James Layton (ed.), Film Atlas. www.filmatlas.com. Brussels: International Federation of Film Archives / Rochester, NY: George Eastman Museum.