Spacevision(1966–1978)

A single-strip over-and-under 35 mm 3-D filming and projection system.

Film Explorer

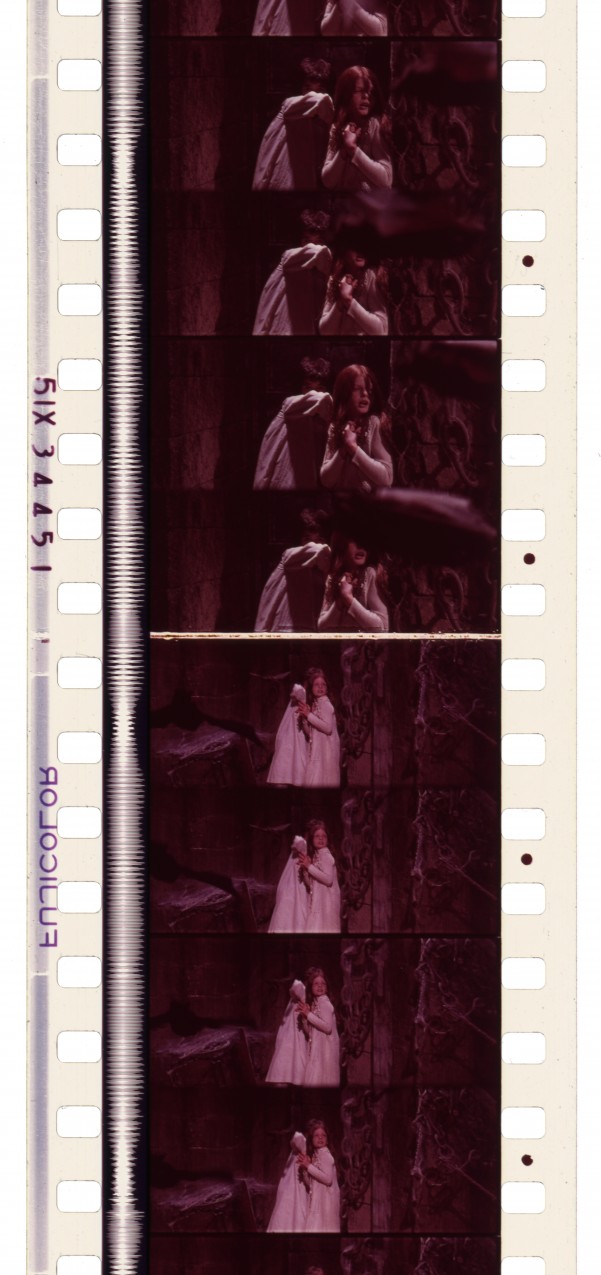

A 35 mm Spacevision print of Flesh for Frankenstein (1974), displaying left-eye (top) and right-eye (bottom) stacked images. Note the reference marks, between the perforations on the right edge, indicating the right-eye subframe.

The Museum of Modern Art, New York, NY, United States.

Images from the camera negative for Flesh for Frankenstein. Note the presence of vertical occlusions at the left vertical edge of the left frame (top), and the right vertical edge of the right frame (bottom). Prints of the film do not show this anomaly, indicating that optical printing was used to correct it.

The Museum of Modern Art, New York, NY, United States.

Identification

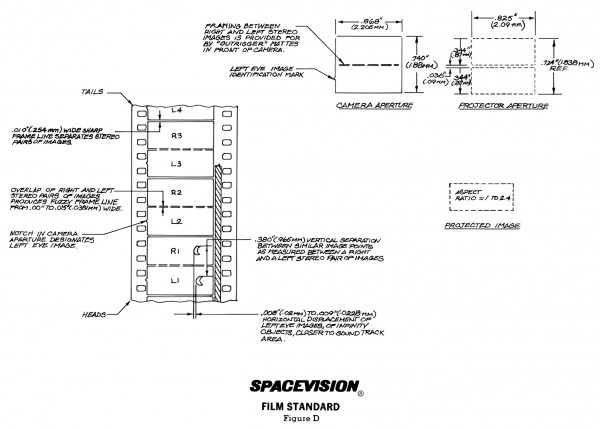

Outer aperture: 20.95 mm x 18.40mm (0.825 in x 0.724 in). Subframes: 20.95 mm x 8.74mm (0.825 in x 0.344 in). Septum between subframes: 0.91mm (0.036 in). Center-to-center distance: 9.65 mm (0.380 in).

Color

Reference marks, between the perforations on the right edge, indicate the right-eye subframe.

1

Original theatrical prints may exhibit considerable fading.

Three-D Effects by ‘Spacevision’

Monaural optical, or magnetic stripe quadraphonic.

Outer aperture: 22.05mm x 18.80mm (0.868 in x 0.740 in). Subframes: 22.05mm x ~9.40mm (0.868 in x ~0.370 in). Septum between subframes: 0 to 0.38mm (0.015 in). Note that image overlap in the septum separating the left and right subframes varied, occasionally reducing the height of each subframe by a marginal amount.

Color

Unknown

History

Before and during World War II, Major (later Lieutenant Colonel) Robert V. Bernier of the US Army Air Forces carried out extensive work on stereo photography and stereophotogrammetry, using sequential stereo photographs taken from moving aircraft to create topographical maps. After the war, Bernier began to pursue the idea of using 3-D motion pictures in training military recruits (Symmes, 1974: p. 433). His earliest experiments filmed and projected the left- and right-eye images in rapid succession, not simultaneously. The results, while impressive, were marred by erratic motion, especially with movements in the lateral plane (Bernier, 1951: p. 320). The system was impractical for commercial cinemas since it required nonstandard projection equipment. Bernier reasoned that simultaneous exposure of the stereo-pairs, and perfectly synchronized projection, were essential for the best results. He continued working on the problem after leaving the US Air Forces in the early 1950s.

Meanwhile, filmmaker Arch Oboler scored a major success with his 1952 jungle melodrama Bwana Devil. Like other 3-D films of that period, Bwana Devil was shown using problem-prone, labor-intensive dual-strip projection. Hollywood soon abandoned 3-D as an active production format, but Oboler stood firm in his belief that three dimensions offered exciting creative possibilities. Over the next decade, he continued to seek a practical 3-D system that employed one camera, one projector and one strip of film. Oboler later claimed to have spoken to as many as a hundred would-be inventors in his search, most of whom he found untrustworthy or unreliable (Koszarski, 2000: p. 19).

In Lt. Col. Bernier, Oboler felt he had finally found a capable inventor with a practical approach to 3-D cinematography. Bernier proposed building a twin-lens image-capturing device to expose left and right subframes, one above the other, on a single strip of 35mm film. Using seed money from Oboler and additional funding from Capitol Records, Bernier built two working models of his Trioptiscope taking lens (Symmes, 1974: p. 448). (According to 3-D expert John Sybenga, a personal friend of Arch Oboler, there were ultimately four potential Trioptiscope lenses that were considered in total [Author’s interview, February 8, 2025].)

Oboler used these working models to make a science fiction feature, The Bubble (1966). Partly to maintain quality control, and partly owing to a limited supply of projection optics, Oboler gave The Bubble a limited roadshow release in selected cities across the United States, beginning Christmas 1966. Carefully staggered distribution continued over several years, resulting in very modest commercial success.

Oboler eventually sold The Bubble to US exhibitor Louis K. Sher, who gave the film bookings in his Art Theatre Guild chain of theaters. Sher later agreed to produce a romantic drama written and directed by Oboler in Spacevision, Domo Arigato (Variety, 1972).

American filmmaker Paul Morrissey co-wrote and directed Flesh for Frankenstein (aka Andy Warhol’s Frankenstein), filmed in Spacevision at Cinecittà Studios in Rome in 1973. Infamous at the time for its unrestrained gore, Morrissey’s film was nevertheless a solid commercial hit, conjuring up $1 million in box-office revenue its first six weeks in just six American theaters (Cassyd, 1974).

Producer Joe Kaufman signed an exclusive deal with Capitol Records with plans to produce a series of concert films in Spacevision (Boxoffice, 1974). Footage of country singer Willie Nelson’s Fourth of July picnic was shot in 1974 but never released, and no other concert films appear to have been shot in Spacevision.

Documentary filmmaker Murray Lerner, commissioned to make a film for Marineland in Florida, decided to employ Spacevision. Described as, “a marvelous example of stereo filmmaking” (Shepard, 1983: p. 40) that, “elevated 3-D to art status” (Tozian, 1982: p. 143), Lerner’s Sea Dream featured extensive underwater footage and impressive off-the-screen 3-D effects. The 23-minute short ran for several years in a specially built theater at Marineland and was later shown at Knott’s Berry Farm amusement park, Buena Park, CA (Lewis, 1987: p. 94).

The technical and commercial success of Spacevision films, especially Flesh for Frankenstein, convinced others that its over-and-under format was a credible industry-wide standard for 3-D. From the mid-1970s to the early 1980s, rival systems with different optics, but near-identical frame architecture appeared, including Optimax III, Marks 3-Depix, ArriVision, and the over-and-under variant of StereoVision. All these systems were used to make feature films in the early 1980s, but Spacevision, which offered only one focal length for photography and could only be used with antiquated non-reflex cameras, went all but ignored. In the mid-1980s, Capitol Records made some effort to upgrade Spacevision for compatibility with reflex cameras while adding a choice of different focal lengths. But this was too little, too late, as by then interest in 3-D theatrical films had once again waned.

Selected Filmography

Feature. An American production filmed in South Korea with a mixed cast and crew. A giant gorilla – portrayed by a man in a patently unconvincing gorilla suit – ravages the Korean countryside, carrying a young American woman (Joanna Kerns) along in the palm of his hand.

Feature. An American production filmed in South Korea with a mixed cast and crew. A giant gorilla – portrayed by a man in a patently unconvincing gorilla suit – ravages the Korean countryside, carrying a young American woman (Joanna Kerns) along in the palm of his hand.

Feature. A young married couple, their newborn infant and a charter airplane pilot find themselves stranded in an isolated town where the inhabitants behave like mindless automatons. The new arrivals soon discover that the town and its surrounding countryside are covered by an enormous, indestructible dome. The Bubble was most widely shown in an edited version, shorn of 21 minutes and retitled Fantastic Invasion of Planet Earth.

Feature. A young married couple, their newborn infant and a charter airplane pilot find themselves stranded in an isolated town where the inhabitants behave like mindless automatons. The new arrivals soon discover that the town and its surrounding countryside are covered by an enormous, indestructible dome. The Bubble was most widely shown in an edited version, shorn of 21 minutes and retitled Fantastic Invasion of Planet Earth.

Feature. A US soldier returning from Vietnam forms a friendship with a young American woman touring Japan. As their relationship deepens, he learns that diabetes threatens her eyesight, lending poignant urgency to her desire to see as much of the country as possible in a short time. A mediocre drama but a fascinating travelogue, the film played only a few engagements in the early 1970s before disappearing. The film was finally reviewed by The Hollywood Reporter, in 1990, and Variety in 1992, following repertory screenings in Los Angeles and London, respectively.

Feature. A US soldier returning from Vietnam forms a friendship with a young American woman touring Japan. As their relationship deepens, he learns that diabetes threatens her eyesight, lending poignant urgency to her desire to see as much of the country as possible in a short time. A mediocre drama but a fascinating travelogue, the film played only a few engagements in the early 1970s before disappearing. The film was finally reviewed by The Hollywood Reporter, in 1990, and Variety in 1992, following repertory screenings in Los Angeles and London, respectively.

Feature. Dr. Frankenstein (Udo Kier) builds one male and one female creature whose progeny he hopes will give rise to a master race. Unfortunately, his male creature is not nearly as interested in sex as the doctor’s own wife (Monique Van Vooren) and her lover (Joe Dallesandro), whose curiosity threatens to derail the doctor’s plans. Flesh for Frankenstein became the second highest-grossing 3-D film of the 1970s (after The Stewardesses) largely on the strength of its outrageously gory violence and its many off-the-screen 3-D effects, including attacking bats and a spear with a bloody organ dangling from the tip.

Feature. Dr. Frankenstein (Udo Kier) builds one male and one female creature whose progeny he hopes will give rise to a master race. Unfortunately, his male creature is not nearly as interested in sex as the doctor’s own wife (Monique Van Vooren) and her lover (Joe Dallesandro), whose curiosity threatens to derail the doctor’s plans. Flesh for Frankenstein became the second highest-grossing 3-D film of the 1970s (after The Stewardesses) largely on the strength of its outrageously gory violence and its many off-the-screen 3-D effects, including attacking bats and a spear with a bloody organ dangling from the tip.

Short. An artfully directed nature documentary originally designed as a special venue attraction at Marineland in Florida. The film is a compendium of spectacular off-the-screen 3-D effects, taking viewers on a brief tour of Florida’s rich coastline, both above and below the surface of the water. The success of this film, both artistically and as a popular attraction, prompted Disney to employ Murray Lerner for their theme park 3-D film Magic Journeys (1981). It was later brought to Knott’s Berry Farm amusement park in southern California.

Short. An artfully directed nature documentary originally designed as a special venue attraction at Marineland in Florida. The film is a compendium of spectacular off-the-screen 3-D effects, taking viewers on a brief tour of Florida’s rich coastline, both above and below the surface of the water. The success of this film, both artistically and as a popular attraction, prompted Disney to employ Murray Lerner for their theme park 3-D film Magic Journeys (1981). It was later brought to Knott’s Berry Farm amusement park in southern California.

An unreleased feature. A concert film capturing Willie Nelson’s second Fourth of July Picnic celebration, held that year at College Station, Texas.

An unreleased feature. A concert film capturing Willie Nelson’s second Fourth of July Picnic celebration, held that year at College Station, Texas.

Technology

Spacevision was the first commercially practical American over-and-under stereoscopic 3-D system (Morgan & Symmes, 1982: p. 59), recording discrete left- and right-eye images on a single strip of 35mm film, one above the other. This made possible good-quality 3-D motion pictures that avoided many of the problems inherent in dual-strip 3-D projection. Negative and release-print costs were roughly equivalent to those for 2-D films, color timing did not require inordinate attention from processing labs, perfect synchronization of the stereo images was practically assured, and a single capable projectionist could show Spacevision films with little trouble.

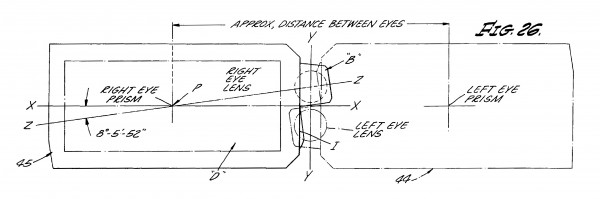

Bernier’s Trioptiscope taking lens was designed for non-reflex Mitchell BNC cameras. Two discrete, spherical lens groups in a common housing exposed two Techniscope-sized frames within a full-aperture 35 mm frame. (Observed in the direction of film travel, the left-eye image is on top, the right-eye image on bottom.) In front of these twin lenses, intricately shaped wide-angle prisms redirected the optical axes so that each captured its image from a slightly different vantage point on the same horizontal plane. A slight rotation of the common lens housing (up to 9 degrees) changed the point where the lens axes converged, defining the plane in space where objects appear to leave the screen and emerge into theater space (US patent 3,531,191). So effective was Spacevision in creating these off-the-screen illusions, that advertising could promise, with only slight exaggeration, that the picture would float off the screen over the audience's heads.

In its earliest theatrical engagements, Spacevision was projected using specially designed dual-prisms outfitted with linear sheet polarizers. These superimposed the stereopairs and cross-polarized them for viewing using linear-polarized 3-D glasses. The only other modification to the projector was an aperture plate cut to the required dimensions and a spherical lens of appropriate focal length and lens brightness selected for the desired screen size. Beginning with Andy Warhol’s Frankenstein in 1974, projection optics originally designed for Chris Condon’s side-by-side Stereovision were modified to handle the over-and-under format, making a wider release possible (Silliphant, 2012: p. 12). As with any system requiring the use of polarizers, a “silver” (i.e., aluminum-surfaced) screen was essential to conserve the linear polarization in the projection beams, on reflection.

Bernier’s projection optics, though of high quality, required careful attention from projectionists to ensure bright, sharp, easy-to-view images. The discrete stereo images on the film could not be projected on the very largest cinema screens, owing to reduced resolution and limited illumination. Only special care would ensure that the left and right images received ample, evenly distributed light.

Some have observed that Spacevision’s Trioptiscope taking lens gave sharper, clearer results than other over-and-under 3-D systems. Vignetting, uneven illumination, focus mismatch and other problems that plagued later rivals were largely avoided in Spacevision. Because the inventor, Lt. Col. Bernier, was present on the set of the two Arch Oboler Spacevision films to act as stereographer and consultant, they strike a particularly good balance among competing requirements for good 3-D, with strong compositions and pleasing use of depth. By contrast, some scenes in Flesh for Frankenstein, filmed without direct oversight by Bernier, exhibit anomalous vertical shadows along frame edges and copious amounts of parallax, which may cause visual discomfort for some spectators.

Spacevision was not without its drawbacks. The availability of only one focal length in the Trioptiscope taking lens, 32 mm, and a single fixed interaxial (lens separation) of 67mm (Williams, 1983: pp. 40–1) imposed creative limitations in cinematography. Close-ups that were comfortable to view could be a tricky matter, and realistic miniature effects shots were practically impossible. Only three focal ratios were available: f/4.5, f/6.3 and f/11 (US patent 3,531,191).

A schematic showing the dimensions of the Spacevision format. Note typos in some measurements (e.g., “2.205 mm” should be 22.05 mm). Note also that 0.009-in (0.228mm) horizontal displacement for “infinity objects” may result in excessive separation on screens larger than 19 ft (5.79m) wide.

Bob Furmanek, 3-D Film Archive LLC, Clifton, NJ, United States.

A schematic showing a front view of the Trioptiscope taking lens. Horizontally displaced prisms at the front of the unit direct light into vertically displaced lens groups at the rear of the unit.

Bernier, Robert V. Three-Dimensional Cinematography. US patent 3,531,191, filed October 21, 1966, and issued September 29, 1970.

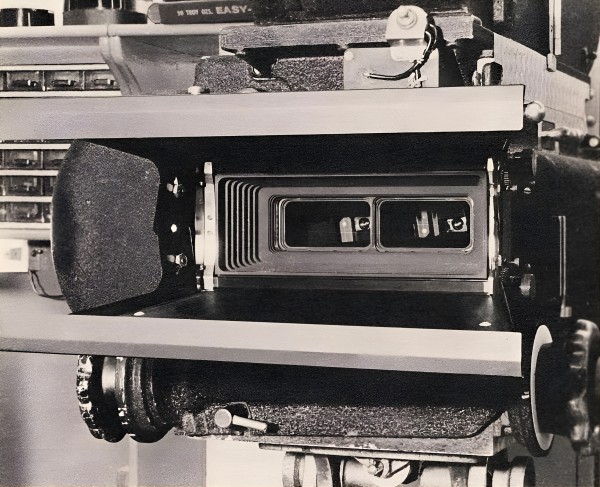

A similar perspective to the schematic above. Note that horizontally displaced prisms at the front of the device convey light to vertically displaced lenses at the rear of the device. The lenses are visible here as recessed circles deep inside each rectangular prismatic “eye”.

Hutchison, David (ed.) (1982). STARLOG’s Photo Guidebook Fantastic 3-D. New York: Starlog Press, p. 49.

The prismatic Spacevision projection unit, mounted before the projection port. Projectors were outfitted with standard-issue projection lenses, selected for desired screen size and brightness. The paired prisms shown here superimposed the left-eye and right-eye images on the screen and cross-polarized them for viewing through complementary 3-D glasses.

Bob Furmanek, 3-D Film Archive LLC.

A stereopair from Domo Arigato (1973), photographed by future two-time Academy Award nominee Donald Peterman (Flashdance (1983) & Star Trek IV: The Voyage Home (1986). The left-eye image is on top.

Bob Furmanek, 3-D Film Archive LLC., Clifton, NJ, United States.

References

American Cinematographer (1974). “The Spacevision 3-D System”. American Cinematographer, 55:4 (Apr.): p. 432.

Bernier, Robert V. (1951). “Three-dimension Movies, in Color”. American Cinematographer, 32:8 (Aug.): pp. 306–7 & 319–21.

Boxoffice (1973). “Seattle”. Boxoffice (July 23): p. W8.

Boxoffice (1974). “Joe Kaufman Now Filming Concerts in 3D Process”. Boxoffice (July 15): p. W2.

Boxoffice (1982). “Spacevision and Murray Lerner: The 3-D Film as Art”. Boxoffice. (November 1): p. 28.

Cassyd, Syd (1974). “Hollywood Report”. Boxoffice (July 22): p. 10.

Gardner, Paul (1974). “Warhol – From Kinky Sex to Creepy Gothic”. The New York Times (July 14): p. 105.

Koszarski, Richard (2000). “‘A Lion in Your Lap – A Lover in Your Arms’: Arch Oboler and Bwana Devil”. Film History, 12:1: pp. 17–28.

Lewis, Randy (1987). “‘Sea Dream’ Film Opens at Knott’s”. The Los Angeles Times (Mar. 14): pp. 94 & 97.

Los Angeles Evening Citizen-News (1967). “New Film Process: Capitol Records Financing ‘Find’”. Los Angeles Evening Citizen-News (January 19): p. A-6.

Morgan, Hal & Dan Symmes (1982). Amazing 3-D. Boston, MA: Little, Brown and Co.

Oboler, Arch (1974). “Movies Are Better Than Ever – In the Next Decade!”. American Cinematographer, 55:4 (Apr.): p. 453.

Shepard, Bill (1983). “3D: Experience and Potential – A Seminar”. Stereo World, 10:5 (Nov./Dec.): 31, 40.

Silliphant, Vicky (2012). The ‘Re-Evolution’ of 3D Movies: 1967–1999. San Diego, CA: StereoVision 3D Systems.

Symmes, Daniel L. (1974). “The Development of the Spacevision 3-D System”. American Cinematographer, 55:4 (Apr.): pp. 432–3, 448–9 & 472–7.

Tozian, Greg (1982). “These Ambitious Films Aren’t from Hollywood”. The Tampa Tribune (Oct. 31): pp. 141 & 143.

Variety (1969). “Oboler Spacevision Up As Medium for H-B Cartoon Feature”. Variety (Oct. 22): p. 24.

Variety (1972). “Arch Oboler Winds ‘Arigato’ For Sherpix”. Variety (Oct. 25): p. 3.

Williams, Alan D. (1983). “3-D Filming Systems”. American Cinematographer, 64:7 (Jul.): pp. 38–41.

Patents

Bernier, Robert V. Three-Dimensional Cinematography. US patent 3,531,191, filed October 21, 1966, and issued September 29, 1970.

Hilbert, Robert S. & Ronald J. Korniski. Three-Dimensional Reflex Lens Systems. US patent 4,688,906, filed December 30, 1985, and issued August 25, 1987.

Hilbert, Robert S. & Ronald J. Korniski. Three-Dimensional Reflex Lens Systems. US patent 4,738,518, filed June 26, 1987, and issued April 19, 1988.

Hilbert, Robert S. & Ronald J. Korniski. Three-Dimensional Reflex Lens Systems. US patent 4,844,601, filed June 26, 1987, and issued July 4, 1989.

Hilbert, Robert S. & Ronald J. Korniski. Three-Dimensional Reflex Lens Systems. US patent 4,878,744, filed June 26, 1987, and issued November 7, 1989.

Followed by

Compare

Related entries

Author

Mike Ballew is a writer and film historian specializing in the history of stereoscopic motion pictures. He is currently working on a book, Close Enough to Touch: 3-D Comes to Hollywood, which tells the story of 3-D movies in the English-speaking world, prior to 1985. He has been employed in television post-production for 25 years.

The author wishes to thank Bob Furmanek, whose deep research into Spacevision for his website, www.3dfilmarchive.com, provided indispensable information and inspiration.

Ballew, Mike (2025). “Spacevision”. In James Layton (ed.), Film Atlas. www.filmatlas.com. Brussels: International Federation of Film Archives / Rochester, NY: George Eastman Museum.