Optimax III(1975–1983)

A single-strip, over-and-under 3-D lens system first devised by Michael Findlay, further developed by Bill Bukowski, and later refined by Carl F. Fazekas for Panavision.

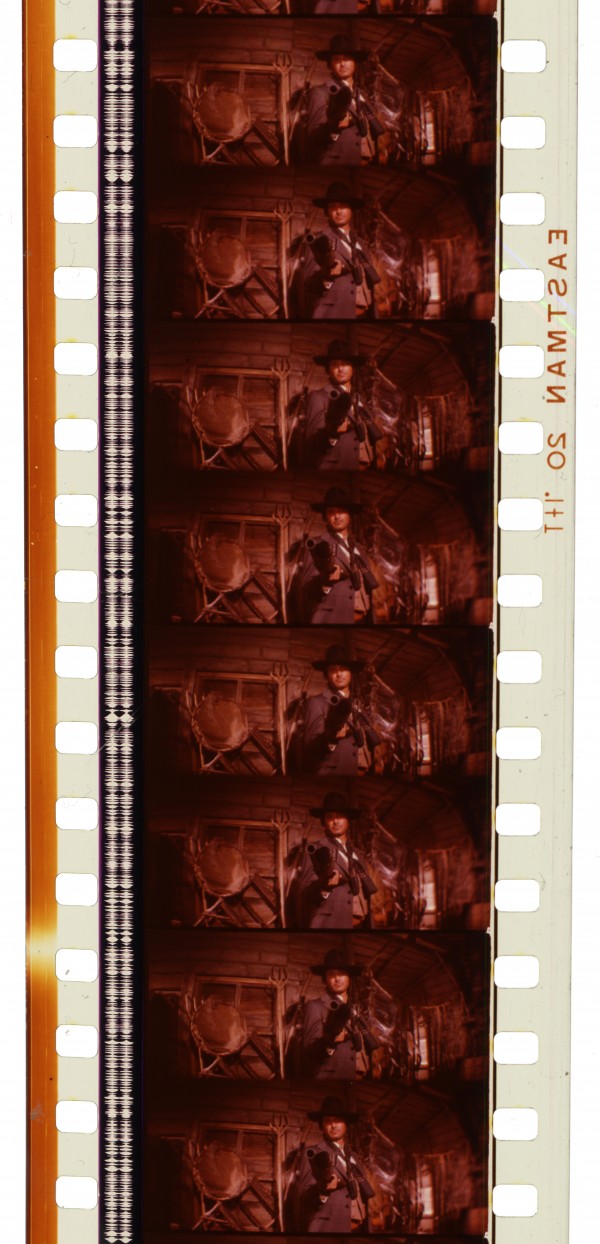

Film Explorer

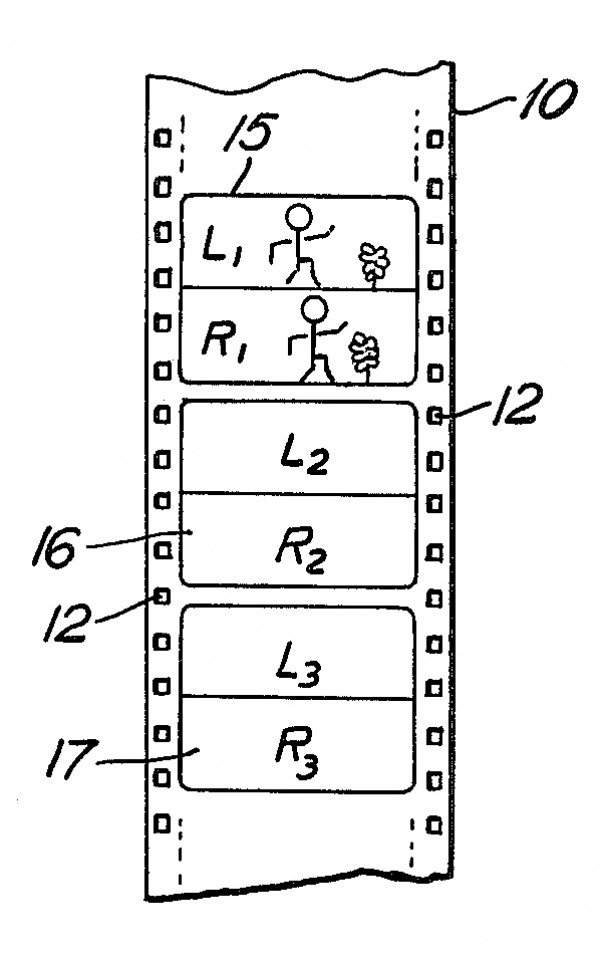

Frames from Comin’ At Ya! (1981) showing the left and right stereopairs “stacked” one-above-the-other, on one strip of film. Note that the slightly thicker frame lines (with subtle rounding at the corners, along the non-guided edge) are defined by the camera aperture, while the thin frame lines are the septum between the left (top) and right (bottom) images.rom Comin’ At Ya! (1981) showing the left and right stereopairs “stacked” one-above-the-other, on one strip of film. Note that the slightly thicker frame lines (with subtle rounding at the corners, along the non-guided edge) are defined by the camera aperture, while the thin frame lines are the septum between the left (top) and right (bottom) images.

National Audio-Visual Conservation Center, Library of Congress, Culpeper, VA, United States.

Identification

(2.367:1)

All known features and shorts were in color.

Unknown – some surviving examples have standard Eastman Kodak markings.

1

Super Touch 3-D, Optimax III

Either mono, or stereo, optical sound; or 4-track magnetic stripe.

Approximately 22.09mm x 18.67mm (0.870 x 0.735 in).

All known features and shorts were in color.

History

New York-based exploitation filmmaker Michael Findlay became interested in 3-D in the mid-1970s. Findlay saw merit in the over-and-under 3-D format, which places left and right stereo images, one above the other on a single strip of 35mm film, inside the area of a standard, full-height frame. The lenses employed in such systems are spherical, not anamorphic, so the resultant frames closely resemble the familiar Techniscope format. Over-and-under 3-D footage may be presented using a standard projector equipped with a suitable aperture plate and a special lens, or lens attachment, to cross-polarize and converge the images onto an aluminized screen, for viewing through polarized spectacles. A number of such projection devices and spectacles were available from rival manufacturers.

Unlike the first commercially successful American over-and-under 3-D system, Space-Vision, which offered only one focal length (32 mm) and one interaxial (67 mm) and was designed primarily for use with non-reflex Mitchell BNC cameras, Michael Findlay envisaged a stereoscopic lens system offering several available focal lengths, a limited but useful variation in interaxial distance and a design fully compatible with the very latest and most popular reflex cameras (Williams, 1983). Findlay called this new system Super Touch 3-D.

Findlay’s friend, exploitation distributor Stanley Borden, offered to fund the development of Super Touch 3-D in return for a share in any eventual profits from the system (Anon., 2019). About 1975, Michael Findlay made the acquaintance of Bill Bukowski, a 23-year-old camera operator and repair technician. Bukowski was able to observe, and occasionally advise, Findlay while the latter developed Super Touch 3-D over the next two years (Bukowski, 2006c). The first commercial use of Super Touch 3-D came with the Christmas 1976 release of Funk in 3-D, a blatantly pornographic film that used test footage made by Findlay with the help of his associate John Amero (Anon., 2019). The film was financed and distributed by Stanley Borden.

Hong Kong-based producer Frank Wong and his associates employed Super Touch 3-D for a series of martial arts features filmed in Taiwan. Findlay was present on the set as technical consultant during the filming of Dynasty and Revenge of the Shogun Women (both 1977). Buoyed by this initial success, Findlay hoped to license the system to other international filmmakers. Tragically, on May 16, 1977, Michael Findlay died, along with four others, in the crash of a commuter helicopter atop the Pan Am building in New York City. He had been on his way to JFK Airport to make the journey to Cannes, France, where he had planned to demonstrate Super Touch 3-D (Edmonds, 1977). After Findlay’s death, the Super Touch 3-D lens system was used in Taiwan for one more martial arts film, Magnificent Bodyguards (1978) starring Jackie Chan.

Ownership of Super Touch 3-D technology passed to Stanley Borden, who remembered Bill Bukowski and enlisted his help in carrying on further development of the system. Bukowski immersed himself in classes at NYU and the City University of New York and consulted with optical engineers in an all-out effort to perfect Super Touch 3-D. In order to keep the inner workings of the device secret, Bukowski brought in his cousin, experienced machinist Janusz Wolny, to help build new prototypes (Bukowski, 2006b).

Bukowski rechristened the lens system Optimax III. In 1980, it was used to film a low-budget Spaghetti Western, Comin’ at Ya!, which did strong business despite largely negative reviews when released in August 1981. Not long afterward, Bukowski and his new business partner, Brud Talbot, raised $650,000 in limited partnerships, much of which was used to buy out Stanley Borden (Cohn, 1981). The new partnership, Optimax 3-D Associates, signed a mutual exclusivity pact with Panavision, which gave the system a thorough redesign in time to make two short concert films, Sweet Emotion and Bitch’s Brew starring the rock band Aerosmith, in December 1982 (Anon., 1983).

The last known use of Optimax III was for the critically panned fantasy-comedy The Man Who Wasn’t There, released by Paramount Pictures in August 1983. According to Dan Sasaki of Panavision, the company still has a complete Optimax III lens unit (Sasaki, 2020).

Selected Filmography

A low-budget spaghetti Western filmed in Spain, notorious for its exuberant use of off-the-screen 3-D effects: Spears, rubber bats, a live snake, pistols, chittering rats, flaming arrows, even a baby midway through a diaper change are all thrust at the audience.

A low-budget spaghetti Western filmed in Spain, notorious for its exuberant use of off-the-screen 3-D effects: Spears, rubber bats, a live snake, pistols, chittering rats, flaming arrows, even a baby midway through a diaper change are all thrust at the audience.

Another period martial arts film, this one elevated by the presence of its young leading man, Jackie Chan.

Another period martial arts film, this one elevated by the presence of its young leading man, Jackie Chan.

A micro-budget pornographic feature cobbled together using test footage shot by Michael Findlay during his initial development of the Super Touch 3-D lens system.

A micro-budget pornographic feature cobbled together using test footage shot by Michael Findlay during his initial development of the Super Touch 3-D lens system.

A fantasy-comedy starring Steve Guttenberg, Art Hindle and Jeffrey Tambor, in which a State Department junior functionary accidentally acquires an invisibility serum and becomes the target of international spies and local thugs. Unlike other examples of Optimax III, the film is often criticized for the undue restraint of its use of off-the-screen 3-D effects.

A fantasy-comedy starring Steve Guttenberg, Art Hindle and Jeffrey Tambor, in which a State Department junior functionary accidentally acquires an invisibility serum and becomes the target of international spies and local thugs. Unlike other examples of Optimax III, the film is often criticized for the undue restraint of its use of off-the-screen 3-D effects.

A martial arts costume melodrama with a period setting, filmed in Taiwan, noted for its copious off-the-screen 3-D effects.

A martial arts costume melodrama with a period setting, filmed in Taiwan, noted for its copious off-the-screen 3-D effects.

Another period martial arts picture made in Taiwan, infamous for its misogyny and brutality. Also known as 13 Nuns.

Another period martial arts picture made in Taiwan, infamous for its misogyny and brutality. Also known as 13 Nuns.

Technology

The Super Touch 3-D/Optimax III system went through several iterations during its decade of active use. The exact construction of Michael Findlay’s earliest unit is not precisely known, but later designs by Bill Bukowski and by Carl F. Fazekas for Panavision give a clear picture of the basic principles.

Findlay and his successors faced the challenge of getting two Techniscope-format frames shot through two lenses with optical axes about 6.5cm (2.56 in) apart onto one band of film in an over-and-under, or “stacked”, configuration. Offsetting the optical axes horizontally was simple, but offsetting them vertically presented a challenge. Additional mirrors or prisms in the light path could diminish image sharpness, brightness and contrast – in addition, some fairly obvious schemes were excluded by existing patents. Findlay decided to sidestep the issue altogether by making one brazen compromise: the right-eye prime lens in his Super Touch 3-D unit would be slightly higher than the left-eye prime. While the center-to-center distance of the images as measured on film amounts to less than 1cm (0.394 in), Bill Bukowski’s patent allows that the lenses could be as much as 13–14mm (0.512–0.551 in) off level (Bukowski, 1984).

This vertical offset in one lens introduces a condition known as vertical parallax. (Note that this is distinct from “vertical misalignment”, which typically involves a uniform vertical offset across an entire image field, unaffected by camera-subject distance.) The left and right images become increasingly out of vertical register as subjects get very close to the camera, but also as subjects move away towards “infinity”. Vertical parallax is milder for subjects in the middle ground, and not present at all at the point where the optical axes of the two lenses converge. In fact, the Bukowski and Panavision units make specific provision to converge the lenses, not only horizontally – standard practice for most stereoscopic systems – but also vertically, so that there would be little to no parallax at the subject of chief interest onscreen.

Bukowski’s iteration put two optical wedges at the front of the device to effect horizontal convergence. Two matched prime lenses, designated “receiving lenses”, captured the left and right points of view. Light from these primes was conveyed through matching field lenses inside the box-like body of the device. A pair of first-surface mirrors behind the field lenses shifted the right-eye image about 3.25cm (1.28 in) to the left, to match the centerline of the film in the camera. A similar pair of first-surface mirrors, just underneath the first pair, shifted the left-eye image about 3.25cm (1.28 in) to the right. The image pairs, now “stacked” vertically, were then conveyed through a single relay lens onto the film (Bukowski 1984). The center-to-center distance of the stereopairs in this design was 0.374 in (9.5mm) (Anon., 1985). Because the resultant images reached the film in an unconventional orientation (rotated through 180 degrees), it was necessary to mount the camera upside down in relation to the lens unit. Otherwise, optical printing would be required to make rectified, projectable prints.

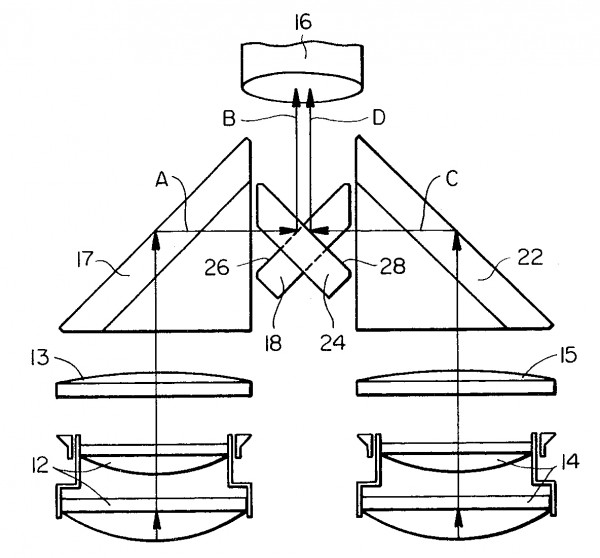

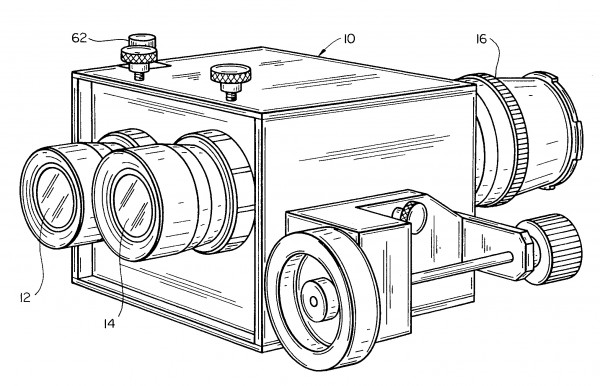

The Panavision redesign replaced two of the four first-surface mirrors with a pair of Amici prisms, with the result that the images reached the film in the conventional orientation and the camera could be used right-way up. In this Panavision redesign, the left-eye lens is now higher than the right-eye lens. Instead of wedge prisms, the Panavision redesign relies on precise horizontal offsets of the right prime lens to effect desired changes in stereoscopic convergence.

The periphery of the combined stereo pairs measures approximately 0.870 in x 0.735 in (22.1mm x 18.67mm), with a “septum” separating the left and right images measuring approximately 30 mils (0.762mm) (Fazekas, 1985). The precise center-to-center distance in Optimax III stereopairs after the Panavision redesign is an open question. The Fazekas patent specifies 0.3675 in (9.36mm), while literature from StereoVision International, Inc., who supplied projection optics for all over-and-under 3-D systems, gives a figure of 0.387 in (9.83mm). (Anon 1985).

Since the Findlay and Bukowski lens units were practically hand-built, and since films made with them were rough-and-tumble exploitation and action flicks, optical components could sometimes jar loose or fall out of alignment. The more than 20 glass surfaces in the Bukowski unit required constant inspection, frequent cleaning and occasional realignment – and this was not always done. Films made using early versions of Optimax III sometimes display chromatic aberration, vignetting, speckling, watermarks, uneven focus, and illumination mismatch between the left and right images, often to a greater degree than may be observed in rival over-and-under format lens systems. The Panavision redesign lessened or eliminated many of these problems.

Bukowski’s upgrade of Findlay’s design offered a 32mm prime lens, with add-on optics to achieve equivalent focal lengths 16, 24 and 64mm. (Bukowski, 2006a; Bukowski, 1984). The Panavision upgrade offered five pairs of prime lenses: 16, 25, 35, 50 and 85mm. (Fazekas, 1985).

The Bukowski and Panavision units offered a small variation in interaxial – that is, the separation between the optical axes of the prime lenses. The minimum separation was 2.031 in (51.59mm), while the maximum was 2.875 in (73.03mm). While stereographers generally advocated a smaller interaxial for closer camera-to-subject distances, in order to achieve more comfortable viewing results, one source somewhat ambiguously states that the interaxial for Optimax III varied according to focal length, suggesting that optical/mechanical limitations of the system dictated the interaxial distance (Williams, 1983). But Bukowski’s patent in particular states that the range of interaxials is meant as a feature to enhance the system’s flexibility in use.

Observed in an upright position, with the soundtrack (guided) edge of the film at left, the left-eye image is on top, the right-eye image below. Raw scans from the film Dynasty display no obvious indexing system (i.e., gate notching, or special inter-perforation markings) to distinguish the left- and right-eye views.

A patent schematic, illustrating the arrangement of Amici prisms (17, 22) and first-surface mirrors (18, 24) in Panavision’s redesign of Optimax III. Note that mirror 24 is positioned above mirror 18.

Fazekas, Carl F. Camera for Three-Dimensional Movies. U.S. patent 4,525,045, filed January 23, 1984, issued June 25, 1985.

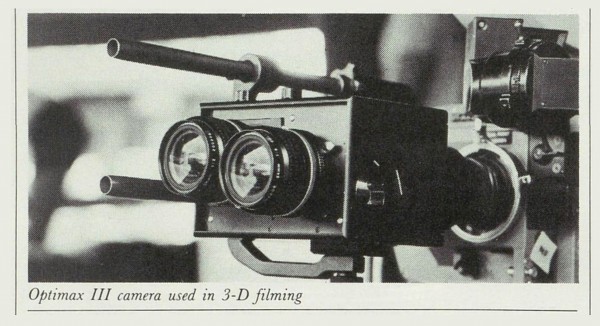

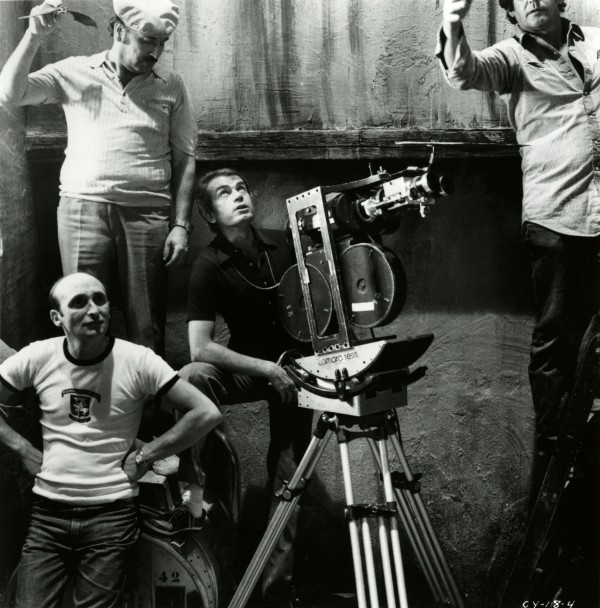

A promotional photograph, from 1982, predating the ultimate redesign of the system by Panavision. Note that the right lens is higher than the left lens in this iteration of Optimax III.

Gilbert, Tom. (1982). “3-D: The New Wave”, The Hollywood Reporter (November 5): p. S-30.

A not-to-scale schematic illustrates how Optimax III “stacked” its stereopairs on one strip of film. All “over-and-under” 3-D systems employed a similar arrangement. Note that the left-eye image was positioned above the right-eye image on the film.

Bukowski, William A. Stereoscopic Lens System. U.S. patent 4,436,369, filed September 8, 1981, issued March 13, 1984.

Optimax III prior to its redesign by Panavision, seen here on the set of Comin’ At Ya! (1981). Note that the camera is mounted upside down.

Film Stills Archive, The Museum of Modern Art, New York, NY, United States.

The Optimax III lens system after its redesign by Panavision. Note that the left lens is now higher than the right lens.

Fazekas, Carl F. Camera for Three-Dimensional Movies. U.S. patent 4,525,045, filed January 23, 1984, issued June 25, 1985.

References

Anon. (1983). “Panavision Pacts With Optimax III For 3-D”. Daily Variety (January 25): p. 15.

Anon. (2019). “Michael Findlay’s Last Year—3-D, Funk, and the Tragedy on the PanAm Building: An Oral History”. The Rialto Report (July 21) (accessed October 1, 2024). https://www.therialtoreport.com/2019/07/21/michael-findlay/

Bukowski, Phil (2006a). “An Interview with Bill”. The Big Bukowski (May 13) (accessed October 1, 2024). http://thebigbukowski.blogspot.com/2006/05/interview-with-bill.html

Bukowski, Phil (2006b). “Out of a Tragedy...”. The Big Bukowski (August 2) (accessed October 1, 2024). http://thebigbukowski.blogspot.com/2006/08/out-of-tragedy.html

Bukowski, Phil (2006c). “Heritage and the Biography”. The Big Bukowski (August 7) (accessed October 1, 2024). http://thebigbukowski.blogspot.com/2006/08/heritage-and-biography.html

Cohn, Lawrence (1981). “King-Hitzig Talking With Atlantic, EA Re 3-D Rock Features”. Daily Variety (October 23): p. 23.

Edmonds, Richard (1977). “They Met in Death: Five Had Diverse Backgrounds”. New York Daily News (May 18): p. 3.

Sasaki, Dan (2020). Email correspondence with Mike Ballew. (July 31).

Stereovision International (1985). “3-D Film Information Sheet”. Stereovision International, Inc.: p. 1.

Williams, Alan D. (1983). “3-D Filming Systems”. American Cinematographer, 64:7 (July): pp. 40–41.

Patents

Bukowski, William A. Stereoscopic Lens System. U.S. patent 4,436,369, filed September 8, 1981, issued March 13, 1984.

Fazekas, Carl F. Camera for Three-Dimensional Movies. U.S. patent 4,525,045, filed January 23, 1984, issued June 25, 1985.

Compare

Related entries

Author

Mike Ballew is a writer and film historian specializing in the history of stereoscopic motion pictures. He is currently working on a book, Close Enough to Touch: 3-D Comes to Hollywood, which tells the story of 3-D movies in the English-speaking world, prior to 1985. He has been employed in television post-production for 25 years.

I am very grateful to Phil Bukowski, whose documentation of his late brother’s work is invaluable to anyone researching Optimax III.

Ballew, Mike (2024). “Optimax III”. In James Layton (ed.), Film Atlas. www.filmatlas.com. Brussels: International Federation of Film Archives / Rochester, NY: George Eastman Museum.