StereoVision (over-and-under)(1976–2003)

A single-strip 35mm over-and-under 3-D filming and projection system.

Film Explorer

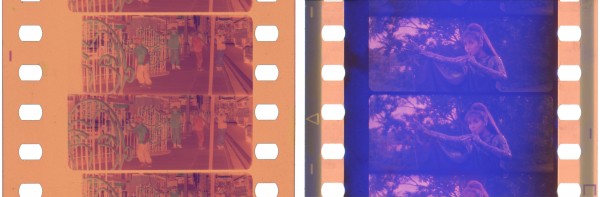

Frames from Metalstorm: The Destruction of Jared-Syn (1983). As with other American over-and-under 3-D systems, the left image is on top, the right image on the bottom. The large amount of parallax on display, for this “in-your-face” 3-D effect, results in pronounced visual disparity between the two images. Note the square markings adjacent to frame lines along the right edge.

National Audio-Visual Conservation Center, Library of Congress, Culpeper, VA, United States.

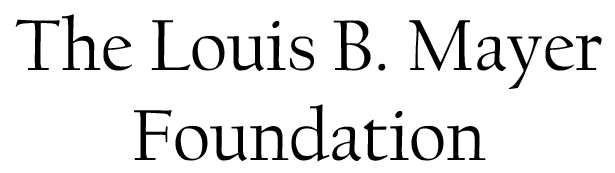

The camera negative of Run for Cover (1995). Note the clearly defined frame lines (with rounded corners), as contrasted with the thin septum separating the left- and right-eye subframes (collectively known as a “stereopair”). Note also the vertical shadow at the left edge of the lower (right-eye) subframe. StereoVision recommended a narrow aperture plate in the projector to conceal such shadows, ensuring sharply defined edges with uniform alignment in each image onscreen.

Academy Film Archive, Hollywood, CA, United States.

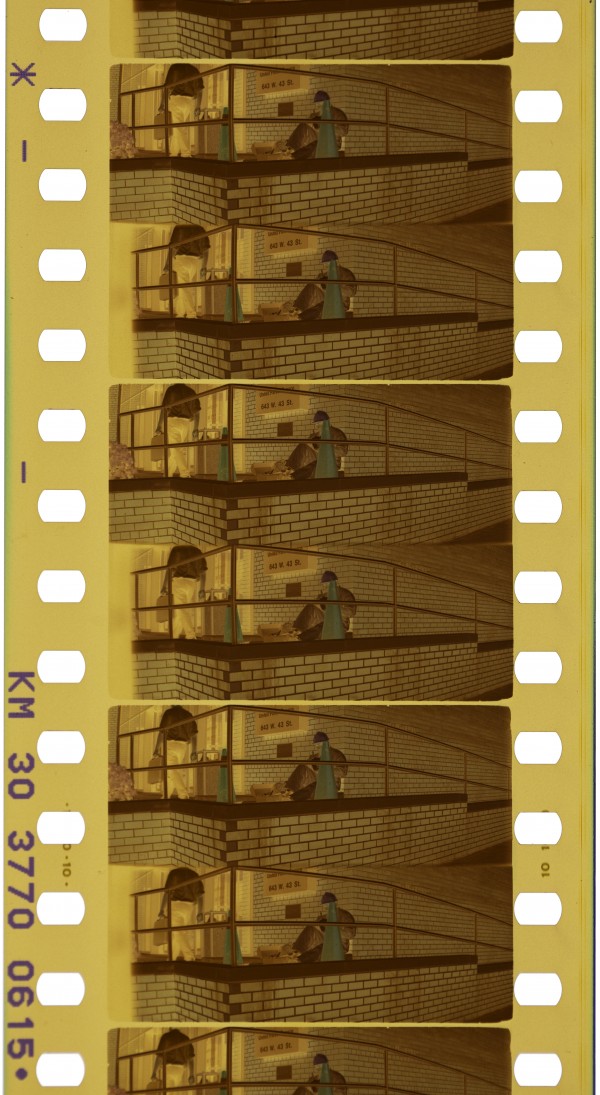

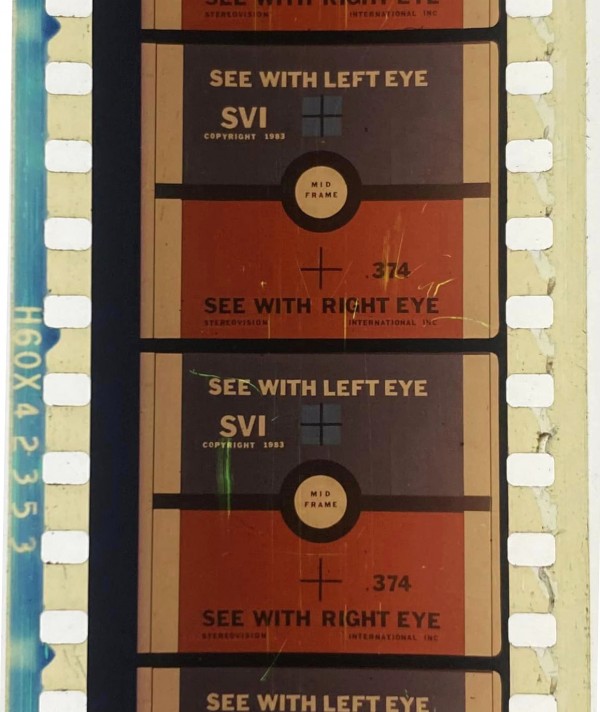

Subframes from the 3-D animated feature Starchaser: The Legend of Orin (1985). While Starchaser was photographed using a standard animation camera with a monocular lens, care was taken so that the 9.5mm (0.374 in) center-to-center distance was fully compatible with StereoVision.

The Museum of Modern Art, New York, NY, United States.

Identification

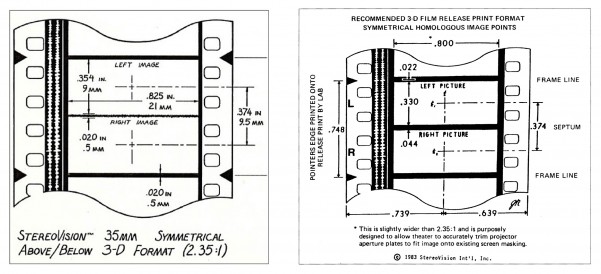

Outer aperture: 20.32mm x 18.40mm (0.800 in x 0.725 in). Each subframe: 20.32mm x 8.38mm (0.800 in x 0.330 in). Septum between subframes: 1.12mm (0.044 in). Center-to-center distance: 9.5mm (0.374 in).

Note that center-to-center distance varies between rival over-and-under 3-D systems. Footage made using one over-and-under camera system cannot always be intercut with footage made using a competing system. When center-to-center distance varies, vertical misalignment in homologous image points will be evident in projection, resulting in potential eyestrain for spectators.

Color

Arrows on reference edge to indicate frame lines; black square markers outside perforations on guided edge to indicate frame lines.

1

Prints made before 1982 may suffer from color fading.

“Stereovision 3-D Camera & Optics Designed by CHRIS J. CONDON” (Parasite); “FILMED IN ARRIVISION 3-D ADDITIONAL 3-D BY STEREOVISION™” (Jaws 3-D); “StereoVision 3-D Lenses by CHRIS J. CONDON” (Metalstorm: The Destruction of Jared-Syn)

Monaural and stereophonic optical.

Outer aperture: 20.95mm x 18.49mm (0.825 in x 0.728 in). Each subframe: 20.96mm x 9.00mm (0.825 in x 0.354 in). Septum between subframes: nominally 0.5mm (0.020 in). Note that the size of the septum separating the left and right subframes varied, sometimes reducing discrete subframe height by a marginal amount.

Color

Standard Eastman Kodak or other manufacturer edge markings.

History

Optical designer Chris J. Condon founded Century Precision Optics in 1948 (Condon, 1980: p. 273). He went on to supply matched camera lenses for use in filming House of Wax (1953) in Natural Vision 3-Dimension (Zone, 2005: p. 8). That film’s striking visuals had a profound effect on Condon, giving him a permanent affinity towards 3-D (Bates, 1986: p. 88), but years would pass before he did any further professional work involving stereoscopic motion pictures.

Condon’s next commercial foray into 3-D came when he and partner Alan Silliphant devised a single-strip system to make a softcore sex film, The Stewardesses (1969), which became a surprise box-office hit (Variety, 1987: p. 214). First called Magnavision, but soon rechristened StereoVision, this early system captured stereo image pairs side-by-side in miniature subframes using twin spherical lens elements and prisms. These were then printed in a side-by-side anamorphic format with a projected aspect ratio approximating 1.37:1.

Flesh for Frankenstein (1974) was filmed using Spacevision, a 3-D lens system in which the left and right stereo images were “stacked” in alternating subframes on a single strip of film. But Spacevision could supply only a handful of projection devices for the film’s release, so the American distributors turned to Chris Condon. Condon modified existing side-by-side projection devices originally built for the release of The Stewardesses to accommodate the over-and-under format (Zone, 2011: p. 4). Flesh for Frankenstein became another major box-office success.

Over-and-under 3-D was clearly emerging as an industry standard in the mid-1970s. Rivals to Spacevision appeared, including Super Touch 3-D (aka Optimax III), Marks 3-Depix and Impact 3-D. Finding these systems overly complicated, Condon devised his own over-and-under lenses (US patent 4,464,028). In keeping with his established brand, Condon named the new system after the old system: StereoVision.

In 1981, Condon’s company, StereoVision International, Inc., entered a joint venture with Deep and Solid, Inc., headed by physicist-turned-filmmaker Lenny Lipton. Under the banner Future Dimensions, their plan was: “to service the film industry with the optics and expertise needed for … a flourishing revival of the stereoscopic medium” (Lipton, 1982).

General Motors commissioned a 12-minute promotional film using Future Dimensions. The Dimensions of Oldsmobile Quality (1981) was shown as part of the US automaker’s two-hour multimedia show for dealer conventions in Reno, NV, Chicago, IL, and Nashville,TN (Cohn, 1981: p. 76).

Future Dimensions next struck a deal with North Carolina-based exploitation producer Earl Owensby (The Durham Sun, 1981). Rottweiler (1981) became the first of six Owensby features filmed in StereoVision.

Independently of Lipton, Condon supplied lenses and technical guidance to outré auteur Charles Band for Parasite (1982), a low-budget monster yarn that brought decent returns despite terrible reviews (Leogrande, 1982). Band followed up a year later with a sci-fi action flick, Metalstorm: The Destruction of Jared-Syn (1983), also in StereoVision and likewise roundly panned by the press.

Producer Rupert Hitzig had planned to use Optimax III for Jaws 3-D (1983), but a thorough on-going redesign of that system by Panavision caused delays and ultimately prevented its use (Gilbert, 1982: p. S-30). Seeking an early start to production, Hitzig and director Joe Alves made provisional use of StereoVision. The first nine days of principal photography employed Condon’s lenses (Condon, 1983a), but the rest was filmed using the newly available Arrivision system, which was preferred by the filmmakers.

Portions of Emmanuelle 4 and the entirety of Venus (both 1984), two French-made softcore skin flicks, were filmed in StereoVision, as was My Dear Kuttichathan (1984), an ambitious children’s fantasy that achieved massive commercial success in its native India.

StereoVision was used only occasionally in the years that followed. Run for Cover (1995), an actioner from Richard W. Haines, and The Creeps (1997), a horror comedy from Charles Band, saw only a few 3-D playdates. A late highpoint for StereoVision came when handheld Steadicam scenes for the Universal Studios theme park attraction T2 3-D: Battle Across Time (1996) were filmed in 35mm using Condon’s lens units (Probst, 1996: p. 44). With the advent of digital cinema in the early 2000s, StereoVision fell into disuse completely.

Selected Filmography

Feature film. A mad scientist, looking to bring archetypal monsters to life, accidentally creates small-scale versions of Dracula, Frankenstein’s monster, a living mummy and a werewolf in this horror comedy.

Feature film. A mad scientist, looking to bring archetypal monsters to life, accidentally creates small-scale versions of Dracula, Frankenstein’s monster, a living mummy and a werewolf in this horror comedy.

Feature film. A free-spirited young woman finds erotic adventures in every corner of the globe. She reconfigures herself using plastic surgery and turns Brazil into her sexual playground. Filmed partly in Arrivision and partly in StereoVision.

Feature film. A free-spirited young woman finds erotic adventures in every corner of the globe. She reconfigures herself using plastic surgery and turns Brazil into her sexual playground. Filmed partly in Arrivision and partly in StereoVision.

Feature film, also known as Gremloids. A science fiction comedy, the sixth and final film in StereoVision from producer Earl Owensby. While earlier Owensby films relied on mostly unknown actors, Hyperspace featured the nationally known American comics Paula Poundstone and Chris Elliott. The film gained cult popularity on 2-D home video in the United Kingdom.

Feature film, also known as Gremloids. A science fiction comedy, the sixth and final film in StereoVision from producer Earl Owensby. While earlier Owensby films relied on mostly unknown actors, Hyperspace featured the nationally known American comics Paula Poundstone and Chris Elliott. The film gained cult popularity on 2-D home video in the United Kingdom.

Feature film. A high-profile second sequel to the 1975 classic Jaws. Arguably the most visible 3-D film of the early 1980s, Jaws 3-D scored popular success in its first week of release but was savaged by critics and soon spurned by audiences. Filmed primarily in Arrivision 3-D, with the remainder in StereoVision.

Feature film. A high-profile second sequel to the 1975 classic Jaws. Arguably the most visible 3-D film of the early 1980s, Jaws 3-D scored popular success in its first week of release but was savaged by critics and soon spurned by audiences. Filmed primarily in Arrivision 3-D, with the remainder in StereoVision.

A Malayalam-language, feature-length children’s comedy fantasy: the first 3-D feature made in India. A mystical genie befriends three children when they release him from the bondage of a cruel sorcerer.

A Malayalam-language, feature-length children’s comedy fantasy: the first 3-D feature made in India. A mystical genie befriends three children when they release him from the bondage of a cruel sorcerer.

Feature film. In a dystopian near future, a criminal dictatorship forces a reluctant scientist to create parasitic monsters that menace the inhabitants of an isolated town. Most notable for its lead actress, a not-yet-famous Demi Moore.

Feature film. In a dystopian near future, a criminal dictatorship forces a reluctant scientist to create parasitic monsters that menace the inhabitants of an isolated town. Most notable for its lead actress, a not-yet-famous Demi Moore.

Feature film, also known as Dogs of Hell. A low-budget horror thriller, the first in a series of 3-D features from North Carolina-based producer Earl Owensby. Fierce dogs trained as “killing machines” by the US military escape into the countryside, threatening the people of a tourist town.

Feature film, also known as Dogs of Hell. A low-budget horror thriller, the first in a series of 3-D features from North Carolina-based producer Earl Owensby. Fierce dogs trained as “killing machines” by the US military escape into the countryside, threatening the people of a tourist town.

Feature film. A Gulf War veteran must stop terrorists planning to attack New York City. Features cameo appearances from Adam West, Vivica Lindfors, Rev. Al Sharpton, Curtis Sliwa and former New York mayor, Ed Koch.

Feature film. A Gulf War veteran must stop terrorists planning to attack New York City. Features cameo appearances from Adam West, Vivica Lindfors, Rev. Al Sharpton, Curtis Sliwa and former New York mayor, Ed Koch.

Feature film. The fabled Greek goddess demands to know why her name and likeness are being exploited to promote suntan lotion. In the meantime, beautiful models frolic in and around the Mediterranean, often wearing little more than sunblock.

Feature film. The fabled Greek goddess demands to know why her name and likeness are being exploited to promote suntan lotion. In the meantime, beautiful models frolic in and around the Mediterranean, often wearing little more than sunblock.

A 12-minute action comedy demonstrating over-and-under StereoVision in its earliest form, released alongside Fantastic Invasion of Planet Earth, a shortened reissue of the 1966 Spacevision film The Bubble. Havoc ensues when a runaway go-kart plows through an unsuspecting neighborhood.

A 12-minute action comedy demonstrating over-and-under StereoVision in its earliest form, released alongside Fantastic Invasion of Planet Earth, a shortened reissue of the 1966 Spacevision film The Bubble. Havoc ensues when a runaway go-kart plows through an unsuspecting neighborhood.

Technology

Chris Condon designed and built stereoscopic camera lenses and projection devices for use with standard 35mm equipment. Like other over-and-under (or “stacked”) 3-D formats in 35mm, StereoVision employs two Techniscope-sized subframes within a full-height, 4-perforation frame. Observed in the direction of film travel, the top subframe holds a left-eye stereo image, the bottom a right-eye image.

StereoVision camera lens units were fairly compact, measuring about 7 in x 9 in (17.78cm x 22.86cm). Early on, StereoVision offered 28mm, 32mm and 75mm focal lengths, each with a minimum aperture of f/2.8 (ASC, 1980: p. 622). Later, these options were expanded to include 15mm, 20mm, 24mm, 32mm, 50mm, 62mm and 90mm (Condon, 1993: p. 535). Each unit had its own fixed interaxial (distance between the axis of each lens), which varied from 1.6 in (40.64mm) to 4 in (101.60mm), “depending on focal length and specifications” (Williams, 1983: p. 40). StereoVision lens units were specifically designed to fit reflex cameras. Originally designed for BNCR mounts, the units could be adapted to other mounts, including Panaflex and Arriflex (Condon, 1993: p. 535).

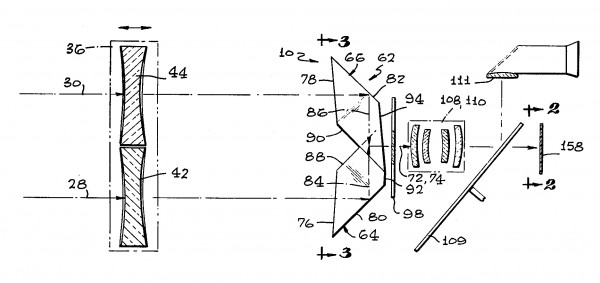

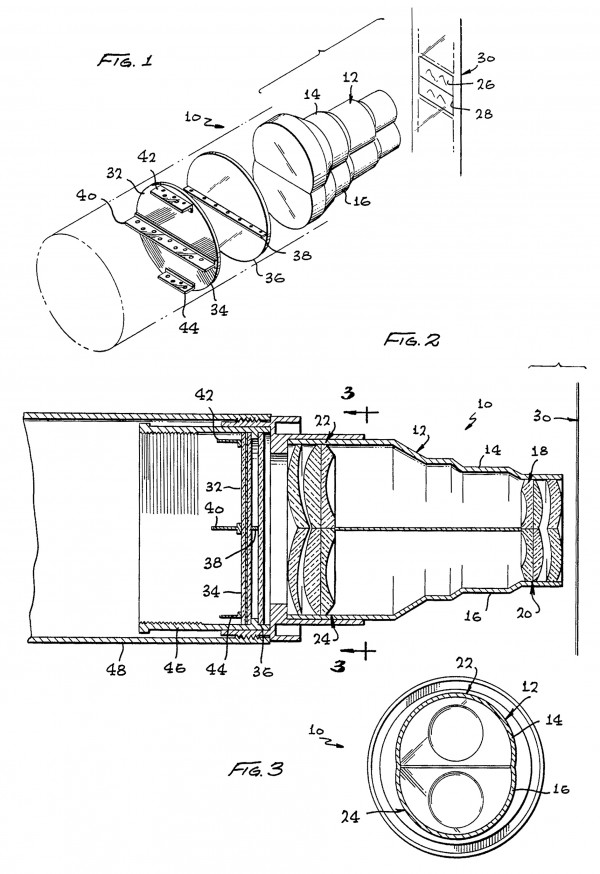

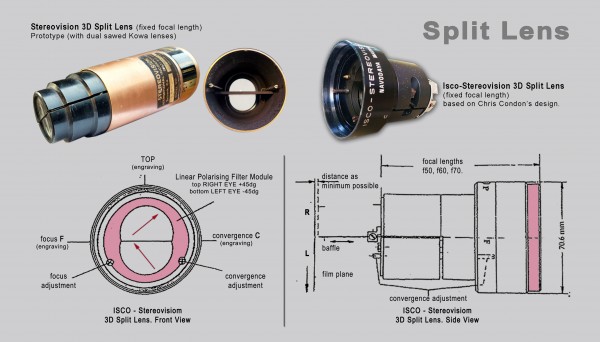

The front optical elements were two adjacent retrofocus lenses. Rhomboid prisms translated the horizontal separation of the optical axes into the tight vertical separation necessary to “stack” the stereopairs on the film. Behind these prisms, vertically mounted dual-lens groups at the rear of the unit focused the images onto the film plane. Small lateral shifts in these rear lens groups effected a change in convergence, centering the lens axes on any desired foreground subject so that it appeared to be at the plane of the screen when viewed in 3-D (US patent 4,464,028).

Focus was pulled using a knob on top of the taking unit. This moved the prisms and front lenses forward and backward in relation to the rear lenses. At close focus range, vertical shadows sometimes appeared in one or the other subframe. Depending on the position of the optics, the septum separating the subframes could become indistinct. Other times, the septum could become tilted at random positions (Punnoose, 2025).

The center-to-center spacing of StereoVision subframes in release prints was 9.5mm (0.374 in), a critical dimension it shared with pre-Panavision Optimax III films and with John Rupkalvis’s StereoScope system. Other systems used different center-to-center spacings (e.g., Arrivision, 9.30mm/0.366 in; Spacevision, 9.65mm/0.380 in) (Williams, 1983: pp. 40–1). To accommodate all standards, Condon produced the Stereoflex, a fully adjustable, low-cost projection unit mounted in front of existing theater projection lenses to show any “over-and-under” 3-D format with minimal adjustments. Using a prism, simple mirrors, and polarizing filters, the stereo subframes were cross-polarized and superimposed on a highly specular (silver) screen for viewing through linear polarized 3-D glasses.

As an upmarket alternative to the Stereoflex, Condon also built integral 3-D projection lenses (US patent 4,235,503) consisting of twin lens groups cut to fit inside a shared barrel and joined along a common chord. Since linear polarizers at the front of the device had to be kept cool to avoid damage, Condon included UV filters and heat sinks to help dissipate excess heat. Early variations had to be customized for particular center-to-center distances (StereoVision International, 1983a: p. 18), but the later “Split Lens Mark III” came with “optical spacing modules” which could be inserted to make the device compatible with center-to-center distances of 0.366 in/9.30mm (Arrivision), 0.374 in/9.50mm (StereoVision), or 0.387 in/9.83mm (Marks 3-Depix) as desired (StereoVision International, 1983b: p. 4).

Condon recommended a special projector aperture plate, “having a septum separating the images” to mask all four edges of the frame and prevent “bleed over”, a potential source of disturbing refractions and image washout. However, light loss was an acute problem: the reduced size of the glass components diminished their focal ratios, the bifurcated aperture plates cut desperately needed lumens, and the linear polarizers consumed as much as two-thirds of available light (Dewhurst, 1954: p. 121).

StereoVision revised its projection specs several times. Principles of Quality 3-D Motion Picture Projection, a manual provided to exhibitors ahead of the release of Jaws 3-D (1983), specifies an aperture size of 0.725 in x 0.800 in (18.4mm x 20.3mm) (Condon, 1983b: p. 3). A slightly later publication, Instructions for Use of the StereoVision Stereoflex Projection System, suggests a similar aperture height but suggests a width of approximately 0.775 in (19.7mm). The 1982 feature Parasite is singled out for a recommended square aperture of approximately 0.725 in (18.4mm) (StereoVision International, 1983a: p. 12).

The StereoVision camera lens unit as seen from below. Note the side-by-side front lens elements (42 & 44), the twin rhomboid prisms (64 & 66) and the lower rear lens housing (110). The upper rear lens housing (108) is obscured from this perspective. Note the relationship of the rear lens housings to a reflex shutter (109) and the film plane (158).

Condon, Chris J. Motion Picture System for Single-Strip 3-D Filming. US patent 4,464,028, filed November 17, 1981, and issued August 7, 1984.

Left: 35mm camera negative of Magic Magic 3D (2003), one of the latest StereoVision productions. Right: 35mm interpositive of My Dear Kuttichathan (1984) made for the reissue of the film in the 1990s.

Jijo Punnoose & Navodaya Studio, Kochi, India. Special thanks to Iyesha Geeth Abbas.

A 35mm StereoVision alignment loop, 1983. Note the center-to-center spacing, clearly marked as 0.374 in (9.5mm). Triangle markers are also visible between the sprocket holes on the left edge to indicate the main frame lines. These are not to be confused with the center septum between subframes (marked with the “mid frame” graphic).

Courtesy of Magnus Rindisbacher.

A Stereoflex Model “A” projection unit. This device made it possible for theaters to project any over-and-under format 3-D film using existing projection lenses. Turning a knob at the top of the unit (partially obscured by cloth) brought the images into alignment onscreen. Note the extension barrel at top left, and the mounting bracket, with knurled knobs at left center, which enabled mounting on a wide variety of projectors.

Eric Kurland, 3-D SPACE, Los Angeles, CA, United States.

A patent diagram of the StereoVision integral projection lens. Note linear polarizers (32 & 34) and UV filter (36). Note also heat sinks (38, 40, 42 & 44): a passive means of dissipating excess heat.

Condon, Chris J. Film Projection Lens System for 3-D Movies. US Patent 4,235,503, filed May 8, 1978, and issued November 25, 1980.

Chris Condon’s split-lens design. The example at upper left was made by StereoVision International, while the one at upper right was built by Schneider Corp., Germany, according to StereoVision specs.

Jijo Punnoose & Navodaya Studio, Kochi, India. Special thanks to Iyesha Geeth Abbas.

Left: A schematic showing the camera frame dimensions for over-and-under StereoVision. Right: A schematic showing the projector frame dimensions for over-and-under StereoVision.

Zone, Ray (2012). 3-D Revolution: The History of Modern Stereoscopic Cinema. Lexington, KY: The University Press of Kentucky, p. 87; Zone, Ray (2011). “Chris Condon’s Deep Legacy”. Stereo World (Jan./Feb.): p. 5.

References

American Society of Cinematographers (1980). “Three-Dimensional Filming”. American Cinematographer Manual. Hollywood, CA: The ASC Press, pp. 622–3.

Bates, James (1986). “3-D Movie Entrepreneur Carries Torch for Flickering Medium”. Los Angeles Times (June 17): p. 88.

Christopher, James (1985). “3-D in India”. American Cinematographer, 66:9 (Sept.): pp. 85–7.

Cohn, Lawrence (1981). “3-D Film Production Continues To Rise; 10 Indie Projects”. Variety (Sept. 2): 1, 76.

Condon, Chris J. (1980). “Modern Telephoto Lenses”. In American Cinematographer Manual (5th edn). Hollywood, CA: The ASC Press, pp. 273–6.

Condon, Chris J. (1983a). “Shooting ‘Jaws 3-D’”. The Los Angeles Times (Jan. 23): p. O95.

Condon, Chris. J. (1983b). Principles of Quality 3D Motion Picture Projection. Burbank, CA: StereoVision International, Inc.

Condon, Christopher James (1993). “Stereoscopic Motion Picture Technology”. In American Cinematographer Manual (7th edn). Hollywood, CA: The ASC Press, pp. 534–7.

Dewhurst, Hubert (1954). Introduction to 3-D. New York: The Macmillan Company.

The Durham Sun (1981). “Tar Heel Plans To Lead 3-D Movie Resurgence”. The Durham Sun (North Carolina) (June 18): p. 14-A.

Gilbert, Tom (1982). “3-D: The New Wave”. The Hollywood Reporter (Nov. 5): pp. S-28 & S-30.

Leogrande, Ernest (1982). “3-D Is Still a Hot Movie Ticket”. The Cincinnati Enquirer (Apr. 14): p. 72.

Lipton, Lenny (1982). Foundations of the Stereoscopic Cinema. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold Company Inc., p. 13.

Probst, Christopher (1996). “Future Shock”. American Cinematographer, 77:8 (Aug.): pp. 38–40, 40a, 40b, 41–2 & 44.

Punnoose, Jijo (2025). Email correspondence with James Layton, Crystal Kui and Iyesha Geeth Abbas (Jan. 13).

StereoVision International (1983a). Instructions for Use of the StereoVision 3D Stereoflex Projection System. Burbank, CA: StereoVision International, Inc.

StereoVision International (1983b). Stereoflex III 3-D Projection System. Burbank, CA: StereoVision International, Inc.

Variety (1987). “All-Time Film Rental Champs”. Variety (May 6): pp. 123, 135, 155, 163, 185, 195, 199, 205–6, 210, 214, 218 & 222.

Williams, Alan D. (1983). “3-D Filming Systems”. American Cinematographer, 64:7 (July): pp. 38–41.

Zone, Ray (2005). 3-D Filmmakers: Conversations with Creators of Stereoscopic Motion Pictures. Lanham, MA: The Scarecrow Press, Inc.

Zone, Ray (2011). “Chris Condon’s Deep Legacy”. Stereo World (Jan./Feb.): pp. 4–5 & 35.

Zone, Ray (2012). 3-D Revolution: The History of Modern Stereoscopic Cinema. Lexington, KY: The University Press of Kentucky.

Patents

Condon, Chris J. Motion Picture System for Single-Strip 3-D Filming. US patent 4,464,028, filed November 17, 1981, and issued August 7, 1984.

Condon, Chris J. Film Projection Lens System for 3-D Movies. US Patent 4,235,503, filed May 8, 1978, and issued November 25, 1980.

Preceded by

Compare

Related entries

Author

Mike Ballew is a writer and film historian specializing in the history of stereoscopic motion pictures. He is currently working on a book, Close Enough to Touch: 3-D Comes to Hollywood, which tells the story of 3-D movies in the English-speaking world, prior to 1985. He has been employed in television post-production for 25 years.

Ballew, Mike (2025). “StereoVision (over-and-under)”. In James Layton (ed.), Film Atlas. www.filmatlas.com. Brussels: International Federation of Film Archives / Rochester, NY: George Eastman Museum.